Take a walk down Donner Way from 24th Street toward Franklin Boulevard. On your left are early 20th century bungalows, many with second-story entrances. On the right are some of the revival styles of the 1920s: Tudors, colonials and stucco moderns. Keep walking and you’ll find houses recently renovated and one built in 1986.

Donner Way, like the neighborhood around it, is a place where changing architectural tastes and technologies have blended together.

For more than a century, people have been building homes in the area, from Victorians to ranch houses, from simple cottages to elaborate mansions.

There is a sense of history to the place. The subdivision names, Curtis and Heilbron, and street names, Portola, Sloat, Donner, Marshall, Curtis, Rochon, Burnett and Markham, recall the state’s and the neighborhood’s pioneers. Four were governors of California: Spanish explorer Gaspar de Portola, the first colonial governor; John Sloat, the first U.S. military governor; Peter Burnett, the first state governor; and Henry Markham, a late 19th century governor.

Mention of the Donner party recalls the extreme hardships early settlers endured. James Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill. And French-Canadian immigrant Napoleon Rochon operated a saloon in the 1870s along what is now Franklin Boulevard.

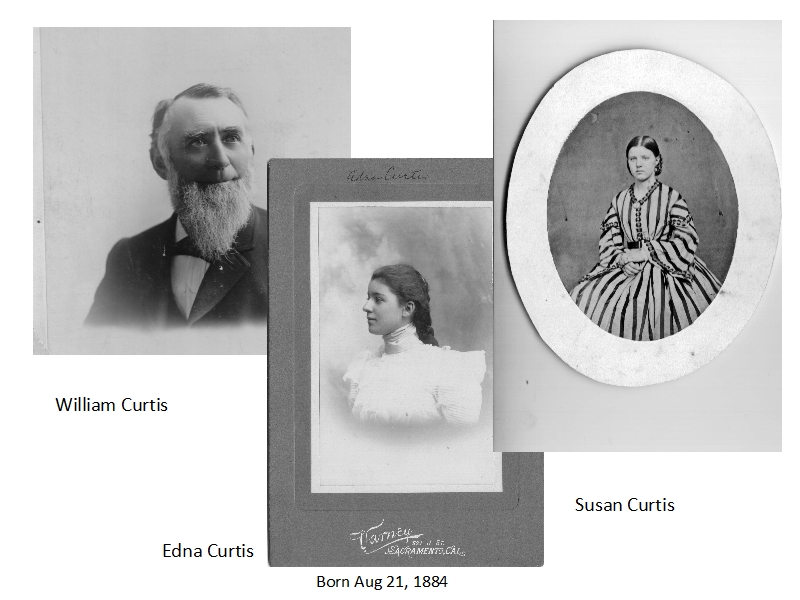

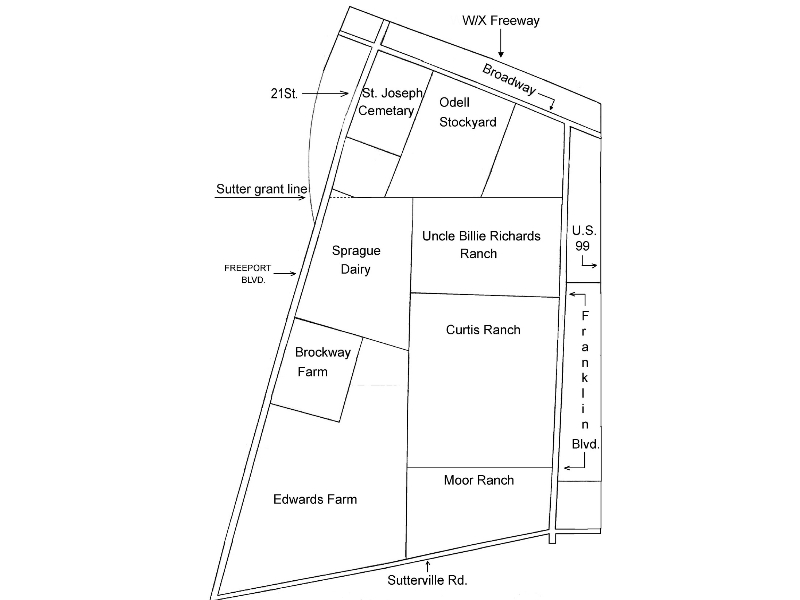

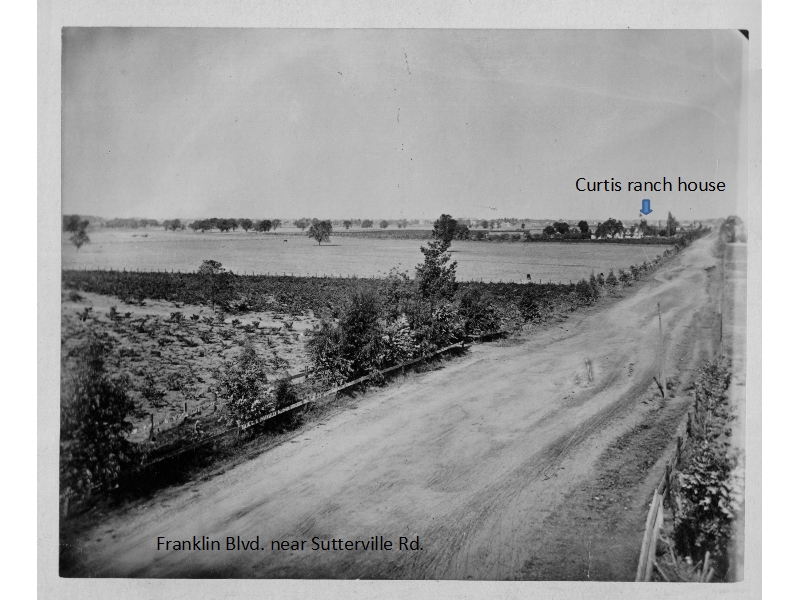

Most important to the neighborhood was wheat farmer and cattle rancher William Curtis. His farms covered thousands of acres in Sacramento County and in Arizona, but the homestead he called his “Home Farm” included about 200 acres between Portola Way and Sutterville Road, 24th Street and Franklin Boulevard. Just before he died, in 1907, Curtis sold the northern edge of his homestead, what would become Portola Way, Fifth Avenue and the north side of Donner Way, which explains why homes there generally are older than homes on the south side.

Curtis Oaks was by no means the first subdivision in the area. In the late 1880s, Highland Park and Ingram Tract had been laid out south of Broadway (then known as Y Street), between St. Joseph’s Cemetery and Franklin Boulevard.

The advent of a municipal power plant made electric streetcar systems feasible, and Curtis Oaks subdivision plans included streetcar tracks of the Oak Park line down the middle of Fifth Avenue.

The pace of development accelerated with West Curtis Oaks to the west of 24th Street. In 1911, the city and its nearby suburbs – East Sacramento, Oak Park, Highland Park, Curtis Oaks and West Curtis Oaks – voted in favor of annexation.

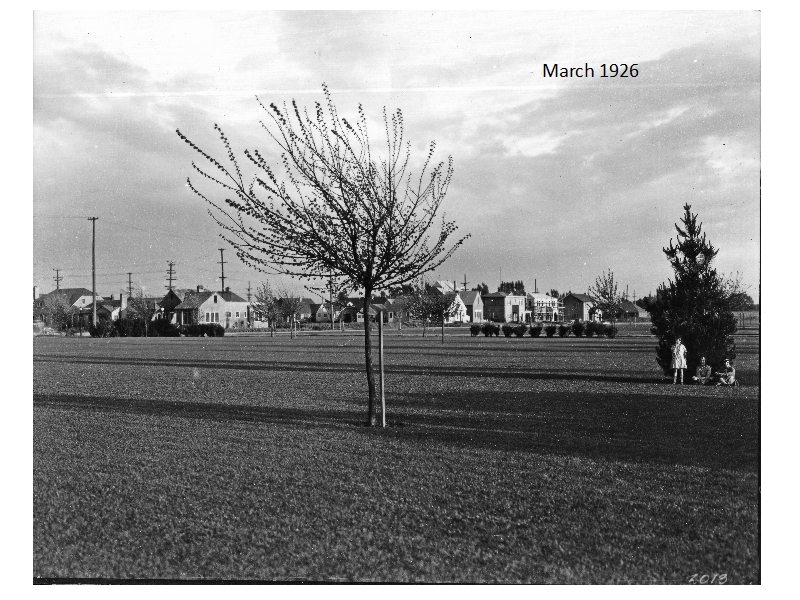

The remainder of William Curtis’ property was developed between 1919 and 1926, in sections east and west of William Curtis Park, which was created down the middle of the former “Home Farm.” Heilbron Oaks was named for cattle breeders Adolph and August Heilbron. The Heilbron Oaks subdivision map, was filed in 1923, included land for Sierra School, which replaced the wood-frame Highland Park School, across the street at 24th Street and Third Avenue, also came from the Heilbron Tract.

With the exception of the Crocker Village development, the neighborhood hasn’t changed much since the 1920s. The trees are bigger and the cars more numerous. Corner groceries came and went, as did a number of gas stations. The original families grew up and out, gradually making way for the next generation and the ones after that.

This article is adapted from a neighborhood history first published with a 1988 SCNA fundraising calendar.